"If I think about the future of cinema as art, I shiver" (Y. Ozu, 1959)

CINEMA PSYCHODRAME (7)/Berlinale 2019 - I Was at Home, But (Angela Schanelec)

Sunday, 28 April 2019 10:23James Lattimer

DARK PASSAGE 1 – Berlin Express (Jacques Tourneur)

Sunday, 26 November 2017 12:37

James Lattimer

BARBARIC CINEMA (1) – Jeannette, l’enfance de Jean d’Arc (Bruno Dumont)

Thursday, 20 July 2017 12:14James Lattimer

GLITTERING FILMMAKERS - By The Time It Gets Dark + The Dreamed Path (A. Suwichakornpong, Angela Schanelec)

Saturday, 19 November 2016 14:40James Lattimer

FESTIVAL/CANNES 2016 – LA MORT DE LOUIS XIV (Albert Serra)

Sunday, 10 July 2016 10:33James Lattimer

Kaili Blues (Bi Gan)

Tuesday, 23 February 2016 12:00The Sort of Song That Plays Only in Your Dreams

James Lattimer

With every first film you watch, you enter unchartered territory. You have no idea what awaits you, you have no experience to draw on and there’s nothing to guide you on your way. You can only give yourself up to the journey and hope the filmmaker is skilled at marking out the terrain; every good filmmaker must also be a good mapmaker. But how do you make a good map if you’ve never made one before? If your map draws too heavily on established routes, the trip is unlikely to be memorable; if it leads too far out into the wilderness, you’re going to lose people along the way. The best maps take you by the hand but still allow you to wander, they give structure but they do not dictate, they mark out paths but allow them to lead anywhere.

Bi Gan’s Kaili Blues spends most of its time charting a series of woozily interconnected trips, between Kaili and Zhenyuan, between past and present, between all the shifting layers of a dream. If, as the Diamond Sutra quote that opens the film suggests, neither the past, present nor future mind can be found, Kaili Blues is about tracking the sublimely futile process of looking for it. This is a place where you see the blue cassette long before it’s actually given to you, where you watch the train that will later return you to Kaili pass through the room in front of you, where there are so many different shots of protagonist Chen Sheng with his eyes closed it’s impossible to determine where one of his dreams stops and the next begins.

So the terrain Bi chooses to map out is an ambitious one. Rather than sticking with the standard three-dimensions of space, he augments his selected swathe of Guizhou province with the additional dimension of time, smearing the boundaries yet further by letting everything be governed by the unruly laws of Chen’s slumbering mind; we shouldn’t forgot he’s a poet after all. It’s thus often hard to say what exactly connects each individual scene, with the temporal, the causal, the spatial or the associative providing equally valid answers, if indeed there is any definitive answer at all. A nostalgic story of keeping hands warm with a torch suddenly cuts to a shot of two unidentifiable hands bathed in red light and tightly clasped together, a motorcycle repair is interrupted by an impromptu piece of bulldozer ballet and when Chen and his nephew Weiwei take a ride in an overgrown amusement park, the camera shows no qualms in detaching itself from their perspective. Just like in Chen’s poems, it’s not about their meaning, it’s about their rhythm.

It’s easy to imagine how all this unbounded freedom might get out of hand and in lesser hands it might, but Bi proves himself to be nothing if not a master mapmaker. His approach to cartography is not about ploughing familiar furrows or leading you up the garden path, but rather scattering the terrain with enough signposts to let you make your own way. These signposts are what other films would relegate to the status of mere objects, they are points of constant reference content to lurk in the background, even as they cut across four whole dimensions and an entire subjectivity. Each insignificant when taken by itself, together they form a lattice that reaches every corner of the film; no matter when or where you might end up, the objects around you offer repose.

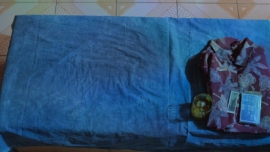

Chen is given three objects to take with him on his way to Zhenyuan - the photograph of a friend of his elderly colleague Guang Lian, the cassette he once gave to her and the shirt she agreed to buy for him - and each get its chance to shine. The contents of the cassette soundtrack Chen’s trip to his mother’s grave; once two replacement buttons have been sewn back on, the shirt is a perfectly familiar outfit to wear in a perfectly unfamiliar place; the photograph is the one way for Chen to know he’s finally reached his goal. These three objects are flanked by countless others: the white dogs that may or may not have taught the locals how to fuck, myriad motorbikes and mirrorballs, blue shoes carried along by the current, pool tables that pop up again despite the camera having shaken off the protagonist, endlessly proliferating watches and clocks: drawn on wrists, painted on walls, covered with a scattering of buttons, spinning back through time as a train passes alongside.

And if all these tangible objects aren’t enough to help you get your bearings, there are more than enough intangible ones on hand to do the same job: the wild men covered in brown hair that are never seen, but seem to be on everyone’s lips, the apparently unmotivated camera movements in the first half of the film whose job it is to prepare you for its wild wanderings in the second, all the facts and figures that make up Kaili stored in the head of a girl who carries the same name as Chen’s wife, her recitations only halted by someone else who also happens to be called Weiwei.

While all these recurring elements function perfectly as signposts, they also resemble the motifs of a perfectly composed song; it’s not for nothing that the film is called Kaili Blues. Perhaps that’s Bi’s most singular achievement, his willingness to rely on rhythm to illuminate an unchartered terrain. How many other first features can you say that about? Much like Chen’s spontaneous final performance, Bi’s is a melancholy number, the perfect soundtrack to a life full of regret, a song that echoes across misty roads, crumbing buildings, dark tunnels and deep valleys, the sort of song that plays only in your dreams.

FESTIVAL/Locarno 2015: Right Now, Wrong Then (Hong Sang-soo)

Monday, 26 October 2015 16:10James Lattimer

As Mil e Uma Noites - Vol. 2, O Desolado (Miguel Gomes)

Sunday, 19 July 2015 10:14A foreign body against the greens, yellows and browns

James Lattimer

Although Arabian Nights is a work of perpetual interpolation, it’s the second volume that celebrates both the pleasure and pain of insertion, for when one thing is put into another, some things change, but others do not. Perhaps that’s what makes The Desolate One so affecting, the slow, aching realisation that however joyful the insertion, it will still be swallowed up by reality sooner or later. Even where there is blood, there will later be pragmatism.

Clad in red, rangy fugitive Simão always feels like a foreign body against the greens, yellows and browns of the Portuguese landscape, despite his best efforts to blend in. At one point, he does indeed vanish into the vista behind him, only to frustratingly reappear shortly afterwards. As Simão roves this austere realm, a string of absurdities is inserted into his wanderings: a donkey dragging Miguel Gomes’ bloodied corpse, a trio of nubile women who offer all the trimmings, a pedalo for pottering across a lake. But all this absurdity comes to nothing in the impassive setting, drowned out by the relentless buzzing of insects, the roar of the wind, the sound of birdsong. It’s no surprise when the landscape finally expels Simão too, his capture as implacable as the air, the rocks and the sun or the lone poplar visible from his cell.

A principled judge must preside over a straightforward matter, the case of a desperate woman driven to sell her landlord’s possessions. Everyday life in a Portugal gripped by austerity, even if this nocturnal assembly is held in an ancient amphitheatre and not all its attendees are human. As the judge probes further, the circle of the implicated only widens: a runaway cow, a yelping pack of unrepentant thieves, a put-upon genie, a mournful olive tree. Yet all these gleeful injections of fantasy fall silent in the face of reality, each happy flight of fancy wrenched back down to earth by another true-life detail of Portuguese suffering. And it’s inevitably one final insertion that brings tears to the judge’s eyes, a note placed in a wallet to replace the money it held, a dignified apology for a theft whose only culprit is the situation itself.

Somewhere among the trees, mist and herds of sheep, there lies a housing estate whose inhabitants are uncommonly sad, grown weary of evictions, rusted-up lifts and the air currents that circulate between the blocks. Yet one day, a mysterious newcomer arrives to lift the gloom, a quiet marvel in the form of a white dog named Dixie. His is a truly beneficent presence which does indeed spread joy, offering comfort to the desperate and uniting the marginalised. But tragedy is an unstoppable force, for even inserting such a perfect machine for loving into this cruel world cannot change its essential nature. Maybe that’s why Dixie must also be a machine for forgetting, shutting out the misery around him so as to continue his mission, the only thing able to confound him being the sheer miracle of his own spectral presence.

Ultimi articoli pubblicati

- 2025-03-24 Chime/Cloud/Serpent’s Path (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

- 2025-03-24 Abiding Nowhere (Tsai Ming-liang)

- 2025-03-24 The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

- 2025-03-24 Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)