"If I think about the future of cinema as art, I shiver" (Y. Ozu, 1959)

Nato a Roma nel 1968 si occupa di bla, bla, bla. Collabora con Skillweb, Lynx e altre società nel campo delle nuove tecnologie di comunicazione.

Appassionato di fotografia, montagna, ecologia e libertà, ASR, subbuteo e bicicletta, grafico e webmaster spesso per lavoro, spesso per piacere.

Tra le sue opere più importanti

- bla bla bla

- bla bla

- bla bla bla bla

Now (Chantal Akerman)

Nell’altro verso del cinema

Vanna Carlucci

Entrare nella notte e trovarsi al centro di un istante. In Now di Chantal Akerman è il QUI assoluto che ci sconvolge, è il qui e ora che ci afferra e ci porta più in là, nello spazio buio dove la velocità della visione (o delle visioni) ci trattiene. Cinque schermi sospesi in aria al centro di una stanza che riprendono fughe, linee perse all’orizzonte, dileguamenti visivi che non segnano un percorso ma impongono dispersioni. Sembra quasi un contraddirsi, ma la Akerman ci spinge in avanti senza indicazioni per portarci oltre il bordo, alla deriva o più in là, nel falsotracciato , nell’altro verso del cinema.

Si scosta la tenda come una palpebra pensando che solo lo sguardo possa aprire una visione (la visione che è palpazione con lo sguardo, direbbe Merleau-Ponty e questo basterebbe a toccarla), ma la trama allarga i propri confini ed è allora che tutto il corpo si muove, nello spazio. Non si tratta di contemplare lo schermo (anzi, gli schermi) per una visione passiva, ma di penetrarlo, quasi sfiorarlo nella fuga di orizzonti imprimendo una certa pressione nell’aria che sembra mancare di staticità e si sposta con noi nel vuoto; farci mobili nella mobilità delle immagini, costringerci a transitare più in là ancora, da uno schermo all’altro, di soglia in soglia e trovarci nell’intermezzo, in quel tra che è un viatico, medium oscuro, nell’insorgenza delle immagini. Sembra quasi che il cinema, questo luogo privilegiato di scontro frontale sguardo-visione, non basti più a sorreggere tutto l’impianto stratificato di un’immagine - edificazione di uno sguardo - ma, in Now, essa ci investe interamente tanto da pensarla fuori da un unico quadro, dal campo del quadro per ritrovarcela ovunque intorno a noi, investiti anche dal fantasma del suono, perché è nel passaggio da uno schermo all’altro delle immagini che la visione prende forma, è in quello spazio vuoto che noi diventiamo ombre buie, vaganti e perse con gli occhi infranti, incapaci di posare l’occhio su quell’attimo frugale che è l’epifania di una visione. L’adesso (Now) non c’è mai perché è già passato, l’immagine passa, scorre ed è già fuori perché lo schermo non è abbastanza, ci vogliono più schermi, il luogo stesso del cinema è anche, ora, fuori dal cinema stesso; non c’è approdo per l’immagine perché non c’è casa, non esiste il luogo che ora diventa punto cieco, ma c’è l’urgenza di scavalcare la distanza che ci separa da questo flusso ininterrotto, migrazione continua lungo orizzonti indefiniti. E la messa in scena diventa messa a punto di supporti sempre nuovi, di terze dimensioni (pensiamo a Godard, Scorsese o all’ultimo Zemeckis) e, ritornando alla Akerman, di nuovi territori (deserti) espressivi che vorrebbero inabissarci nell’interstizio informe della materia che manca continuamente al nostro sguardo: l’eterna incompiutezza di una veduta. Quello che la Akerman sembra chiedersi mentre fugge via con lo sguardo lungo paesaggi completamente vuoti, assenti, è cosa sia il cinema se tutto oggi è cinema, se non sia necessario invece destrutturarlo una volta per tutte e ritornare a cercarlo.

Chi/Mr. Zhang Believes (QIU Jiongjiong)

Tempesta di nuvole

Luigi Abiusi

Chi (Mr. Zhang Believes) del cinese Jiongjiong Qiu è ulteriore, eccedente conferma di un cinema che riflettendo sulla stringente, ottusa contingenza (nelle cui pieghe si sedimenta l’enunciato politico, civistico, etico), non può fare a meno di riflettere su se stesso, sulle proprie possibilità di essere rispetto al tempo; di riflettersi come dispositivo di inerzie, attriti, parvenze che trovano linfa nella storia (verso cui cerca la massima rispondenza), pur destrutturandola in eco, cicaleccio, intreccio di scene riverberanti (di oscurità e voci, canzoni) in un teatro di posa, quale luogo di composizione ed elezione dell’opera, cioè una sorta di “gioco del mondo”. Wang Bing, quello, mettiamo, di Jiabiangou, è stato metabolizzato nell’ibridazione del quadro, di cui Jionjiong Qiu conosce i dis-limiti (Bressane), venendo dall’arte figurativa, qualcosa come “aprire un dissipario per l’arcano” (De Barros), la funambolica fenomenologia di palcoscenici che rimandano uno all’altro compenetrandosi strettamente eppure slegandosi e aprendosi come voragini fuori dal tempo. Anzi, un soqquadro, accostando la mimesi di un acciottolato, il suolo permeato di un’acqua di pece, con lo scenario più artato, costruito, che rivela la sua manifattura, dando proprio per questo profondità simbolica alle immagini, montate secondo un meccanismo di drappi, tendaggi astraenti gli sfondi (storici), a fare da contrappunto a sequenze documentali in cui Zhang Xianchi racconta il suo calvario iniziato nel 1957 con l’accusa di essere un reazionario, ma in effetti già agli inizi degli anni ‘50 (stesso periodo mostrato da Jiabiangou), quando ancora studente e intriso di letture comuniste, si scontra con suo padre, filogovernativo, fuggendo di casa.

Qui l’ipertensione delle immagini, tese nei movimenti acuti, finti delle sagome sul proscenio (un espressionismo di bianco e nero catramoso, che intacca anche i siparietti ironici), si allenta nella naturalità di Zhang Xianchi che di fronte alla macchina da presa racconta la sua vita, per divenire stasi contemplativa e dolente di fotografie poste sulla ghiaia, o quadro nero, Nulla, su cui scorre la voce del protagonista: un amalgama di materiale composito che si declina di volta in volta intorno ai limiti fisiologici dell’immagine cinematografica tentandone il tessuto fantasmatico, inerziale, e l’origine (destino) di fissità, per “aprire il dissipario” (questa sua irriducibilità), come avveniva nell’Erice di Centro Historico o nell'Immagine mancante di Rithy Panh in cui il contrappunto (dialettico, riflessivo, retroattivo) al movimento era dato da riprese su presepi popolati da statuette di creta.

È questa oscillazione, questo movimento a strappi della macchina-cinema, nella nebulosa della materia temporale, a dare senso, pur nel dissesto, a Mr. Zhang Believes, tra fughe in avanti e retrospezione sul proprio nulla; e non è un caso che una delle sue apparizioni la chiami “tempesta di nuvole”: una fitta nebbia verde, in cui la Storia si perde, restando solo un’eco nel buio, uno sgocciolare, uno scricchiolare d’assi, inveterato.

In omaggio all’arte italiana! (Jean-Marie Straub)

L’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua ricerca di una lingua

Lorenzo Esposito

Ancora una volta è Jean-Marie Straub, giustamente duro e giustamente caustico, a ricordarci che dopo l’era della riproducibilità tecnica, l’unico modo per avvicinare ciò che chiamiamo arte è nella non-riproducibilità (Renoir, sempre Renoir), cioè forse in uno spazio, tanto resistente quanto misterioso che si installa fra parola e immagine e il cui nome è lingua. Nuovo titolo: l’opera d’arte nell’epoca della sua ricerca di una lingua. Lingua significa qualcosa impossibile a dirsi diversamente se non come tale, la quale anzi, se fosse o se ambisse a diventare un linguaggio, se avesse intenzioni rappresentative (o, peggio, artistiche), sarebbe una lingua (e infatti oggi lo è sempre più) già del tutto compromessa.

Ecco allora le forze in campo: sceneggiatura come colata grafica, l’immagine come partitura della partitura, memoria puntigliosa del lavoro quotidiano, il cineasta che diventa pittore e musicista, il film come campo di battaglia che include due, tre, quattro versioni del film stesso (perché “Il n’y a pas une meilleure prise”). Oppure, semplicemente, il film installerà parte di sé. Come? Chiedendo a uno come Amir Naderi, che di scenari multiversi se ne intende, di andare a rifilmare ciò che rimane dell’ultimo rullo di una copia del MoMA di Lezioni di storia (con il dialogo da Gli affari del Signor Giulio Cesare di Bertold Brecht, quello dove risulta chiara non solo la natura truffaldina delle italiane genti, ma forse proprio la truffa insita, o il rischio di tradimento connesso all’intenzione artistica in sé). Dove? In una casupola, che sembra una cosa a metà fra una cappella e una cabina di proiezione, posta all’entrata del padiglione italiano della Biennale Arte 2015, aperta da ogni lato (perché in una sala cinematografica si può entrare, ma anche uscire), e in cui al loop del rullo in fin di vita o vivo per miracolo, fra salti della pellicola e definitivi scioglimenti del colore, risponde la recinzione sonora dei materiali (il dialogo brechtiano nell’originale tedesco) e quella visiva delle riproduzioni del testo lavorato alla loro maniera da Straub e Huillet.

Il problema, è chiaro, di questo Omaggio all’arte italiana! (prodotto dalla neonata Zomia di Donatello Fumarola e Alberto Momo insieme a Belva Film e Atelier Impopulaire) non è disquisire su cosa sia arte e cosa no, ma di ricostruire la nervatura del lavoro materiale e testuale del cineasta (compresa la successiva possibile degradazione, la quale ha a sua volta a che fare col supporto e col supporto del pubblico), ricostruirla fino a ridarne la cadenza profonda, conquistandogli quello spazio che, d’altra parte, ne è il carattere.

Allora, questo spazio, è ancora lo spazio del testo, o qualcosa di completamente inedito? E cosa rimane del cinema? Può addirittura partecipare al rischio atmosferico connaturato al filmare stesso? Può essere ancora come la nuvola, come il colpo di vento, come il sole? Può essere il colpo di dadi? Non è in fondo il testo, una volta, per così dire, estratto e ridotto all’essenziale, il luogo verso cui si deve ritornare, certo molto cambiati, ma sempre tesi al reperimento della materia all’origine? Come diceva Danièle Huillet: “È un dettaglio… ma non ci sono dettagli!”.

Out on the Street ( Jasmina Metwaly and Philip Rizk)

Tout va bien in Egypt

Lulu Shamiyya

I get to watch Jasmina Metwaly and Philip Rizk’s Out on the street (Barra fel shari', 2015) in a post-revolutionary summer in Cairo. Tahrir Square is few miles away. I can just imagine the sound of the silence coming from down there: the silence of the everyday life that seems to be back on track. Today, out on the streets of Cairo there’s nothing than just the usual chaos of a megalopolis’ daily routine emptied from the imprévu once brought by a different kind of chaos, that of the revolution. Yet Out on the street reminds me that things never sleep in Cairo, not even the revolution.

A group of working-class men is invited on a Cairo rooftop to join an acting workshop aiming at staging a mise-en-scene of their factory and the power dynamics revolving around it. Police brutality, corruption, abuse of power, exploitation of the workers by their employers, threats of loosing jobs and being put out on the street: everything emerges during the rehearsals, everything is filmed by Metwaly and Rizk’s discreet camera. Quite soon the space of fiction given to the workers to recreate their daily struggle turns into a real space. Once being understood, the mechanism of exploitation is replicated and reproduced by the workers on other workers, as if it were the most natural thing: the mise-en-scene of the abuse becoming the abuse itself. Like in the hall of mirrors, exploitation is exercised from capital on the worker, and from the worker on another worker, and then on another worker, too. The filmmaker is there to witness and document, but has also to join the struggle.

This reminds of another factory, another time, another class struggle. France, 1972: Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin had just filmed Tout va bien, a caustic account of a strike at a sausage factory. At the time, Godard said in an interview1 that he was interested in looking at the social forces simultaneously at work in the same physical space: capital, the working-class, but also the leftists, the engaged intellectuals. One of Godard and Gorin’s main focus in Tout va bien was, in fact, the role of themselves as filmmakers in narrating the workers’ struggle and finding ways to support it. That is why Tout va bien is not so much a film about a workers’ rebellion against capital; rather, it documents the efforts of two engaged intellectuals in approaching this very struggle through cinema. How do we turn a revolution into a filmed image, into a spoken word, without having that same image, that very word betraying the revolution itself? How can a representation not violate the thing represented?

In the aftermath of the 2011 uprising, Metwaly and Rizk, who are members of the media collective Mosireen, raise this question again by asking the Egyptian workers to be their own metteurs en scene. Visually the film mixes together different sources of material (fictional performances taken from the acting workshop, interviews with the workers, personal mobile footage shot by a former factory employee). But what really blurs the line between factual and fictional, between the representation and the thing represented is the workers’ own mise-en-scene of their working condition, of the exploitation they are exposed to which they unconsciously get to replicate. Godard’s words in 1970s France resonate in 2010s Egypt: “the very medium we use was, up until now, in the hands of those we're fighting right against. Therefore, despite our good intentions, we don't completely control it”.

There were millions of cameras switched on the Egyptian revolution in 2011. The medium was in the hands of the people: yet, who controls the images of the revolution once they are generated? Who keeps them, preserves them, and makes use of them?

“Who directs today in France, who is the metteur en-scene” asked Godard in 1972.

“How dare we trade in images of resistance” asks Mosireen in Egypt 2011.

The charm of Metwaly and Rizk’s film lies in the question it raises about their own role as activists and filmmakers. It is as if they could not decide whether being with the workers and supporting the latter’s mise-en-scene to create a narrative of their oppression in order to counter-act the will of the exploiters to put them out on the street again, jobless and without dignity. Yet, at the same time, we feel that they would rather, as filmmakers and activists, be themselves out on the street, looking for the right image, for the right to the image. The one image that would not generate a cycle of “an industry of empathy”2, compassion, pity, solidarity with the revolution; but would, instead, drag more bodies out in the street.

2 Mosireen, Revolution Tryptich, p. 48 in "Uncommon Grounds: New Media and Critical Practice in the Middle Est and North Africa" edited by Anthony Downey, I.B. Tauris 2014

Gli uomini di questa città io non li conosco – Vita e teatro di Franco Scaldati (Franco Maresco)

Making someone exist

Boris Nelepo

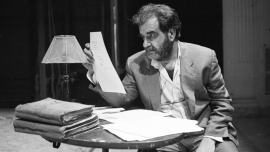

As the founding father of the Cinico TV, since the early 1990s Franco Maresco has been braiding together a cinematic chronicle of his native Sicily and, above all, hometown of Palermo, performing for his homeland the same duty documentarian Peter von Bagh served to Finland, or Želimir Žilnik to the former Yugoslavia and Serbia. This kind of history couldn’t be written without appeals to certain exemplary individuals, so Maresco’s latest, Gli uomini di questa città io non li conosco – Vita e teatro di Franco Scaldati, bears a dedication to Franco Scaldati, the grim theater director and playwright, "the Beckett of Palermo" who once reformed the language spoken on stage as he smuggled in the Palermo dialect along with the local color.

Scaldati’s body of work represents an act of relentless resistance both to the political degradation of his country and to the intellectuals’ comfortable partisanship. In the late 1970s, at the peak of political turbulence, he abandoned the social radicalism of his early plays for the pure poetry of Lucio, a tale of a naive philosopher who converses with the moon, which alienated from him the communist sympathies. Tired of being broke for years, neglected by cultural institutions, and relegated to basement venues, Scaldati at last found employment at Palermo’s major theater, Biondo, much to the chagrin of the bourgeois snobs craving a nonconformist poster boy. Be that as it may, there he remained a hired hand, unable to produce his own plays until the late 1980s when he finally managed to launch Il Piccolo Teatro, a company as independent in spirit as it was short-lived. In his later years, Scaldati almost gave up on his vocation and limited his public appearances to recitals of his new works, mostly comprising phonetic games. Perhaps disillusioned with the idealistic view on art’s global mission, he nevertheless continued to engage in direct activism: for over a decade, Scaldati ran an acting lab for at-risk youth. Rather than dream of "making a difference" with his art, or worry over the artistic results, he simply relished the experience of interacting with people who couldn’t fathom a life outside their bad neighborhoods.

I Don't Know Anyone in This Town is an especially personal and intimate project for Franco Maresco, who considered Scaldati, deceased in 2013, a friend, a teacher, and a mentor (last year he even put on a standard-Italian production of Lucio). Scaldati himself dabbled in acting appearing in several movies by the Taviani brothers and Giuseppe Tornatore, but it was Maresco who captured in full his penchant for comedy in The Return of Cagliostro. The principal ambivalence of I Don't Know... lies in the fact that on the surface, it looks like an ordinary documentary, as good as made for TV. One of the most truly singular filmmakers working today, Maresco chose to forego any kind of authorial voice or personal style, so the Venice audiences, by and large, dismissed the festival’s greatest masterpiece as a strictly provincial narrative handled too conventionally. What does it matter, though? After all, Maresco’s Scaldati, whose existence had almost escaped us but didn’t, is a much more compelling character than most fiction has to offer. Making someone exist – isn’t it as ambitious a task as today’s filmmaking can tackle?

Of course, just like Maresco’s masterful Belluscone. Una storia siciliana released last year, I Do’'t Know... tells a story of defeat - an individual’s, a country’s, art’s, Franco Maresco’s own. Only once did Scaldati enter the Biondo Theater through the main doors as his casket was carried inside to the sound of politicians rhapsodizing about "losing the living embodiment of Palermo’s soul." Two years later, Maresco comes to the theater to ask its audience members if they’ve ever heard of Franco Scaldati. No, no one has. However, the film’s epigraph perfectly encapsulates what Scaldati had to say on the subject: “Beauty is of the defeated. The future is not of winners, it is of those who are able to live”.

Yolo (Ben Russell), The Exquisite Corpus (Peter Tscherkassky), It Seems to Hang On (Jerome K. Everson)

À rebours

Lorenzo Esposito

Il corpo dell’immagine. Ecco qualcosa che tutti cercano (o si immaginano, o sognano), ma che sfugge a qualsiasi defiinizione non supportata da esempi specifici. Eccone ben tre. Corti e cortissimi. Che, anzi, proprio nella forma breve individuano il piano inclinato in cui far convivere quel movimento compresso ed elastico, imploso e deflagrato che forse costituisce il misterioso corpo dell’immagine.

Insomma, si tratta di tracciare i confini di una nervatura invisibile, convogliare l’elettricità di un mutamento sussultorio e continuo, esporsi a una sovraesposizione accecante, ma allo stesso tempo tentare l’inserimento nella piega che scivola fra due ombre, in cerca della zona opaca, del margine insepolto dell’immagine.

Filmare l’infilmabile, ecco di che si tratta. Curiosamente, per tutti e tre i film, il punto di partenza di questa operazione impossibile restano i corpi veri e propri, un bilico necessario al ritrovamento di fisicità, flagranza, possessione. Per questo, come in Yolo di Ben Russell, quel che si pensa essere il proprio film, si scopre essere opera collettiva (filmata nel lontano Sudafrica con il collettivo Eat My Dust), un mash-up capovolto, dettaglio di un dettaglio filmato da altri e visto all’incontrario, a testa in giù. Il cielo al posto dei volti, facce al posto delle nuvole, dialoghi spezzati presi alla fine e in cerca dell’inizio, il centro celato di questa regione sconosciuta (ancora e sempre Michael Snow docet). E tutto come se fosse la prima e ultima volta, l’immagine dipanata in filigrana e insieme distorta, deragliata, un lampo filmato da uno, nessuno e centomila cineasti. “Oh humanity, You Only Live Once!”, così chiosa Russell.

Se poi i corpi sono nudi, allora l’astrazione avverrà sul corpo stesso della pellicola, lavorata in modo che perforazioni e penetrazioni, pelle nuda e pelle di celluloide, diventino un corpo unico, altrettanto insondabile, sonoro, eccitato e sovraesposto frame by frame, incollato e strappato, appunto surrealisticamente squisito (e qui Maya Deren docet). The Exquisite Corpus monta, ma sarebbe meglio dire cerca un ritmo, una sequenza inconsueta, nelle variazioni hard e soft core o di semplici film nudisti di cui viene estratto e manipolato il footage. Procede per immersione, comincia con un semplice film nudista e lentamente si avvolge su se stesso, fluido e vertiginoso insieme, riavvolto nella sua stessa grana, fino a filmare una sorta di erotismo della pellicola più ancora che i lampeggiamenti hard che si sovrappongono con veemenza fino all’accecamento (non so se Tscherkassky conosce Piero Bargellini, ma il riferimento non può non essere il capolavoro Trasferimento di modulazione).

Allora, cos’è più vero, il corpo umano o il corpo dell’immagine? Everson con It Seems to Hang On si avvicina al nucleo della questione facendo slittare il ritmo sovraeccitato e psicotico di due famosi serial killer (la cui storia è dunque vera) direttamente sulla struttura del film: singultante, asimmetrica, continuamente interrotta e raddoppiata, smarrita nell’ossessione, nella ripetizione, nel ghigno senza costrutto, rabbioso e impersonale. Loro uccidono, ma non vedono che così spazio e tempo prima si annullano e poi si incrinano, e alla fine non resta che un grido rivolto al vuoto. L’immagine è il suo stesso corpo separato, la ballata atonale di una spossessione.

Tela brilhadora - O Garoto (Julio Bressane)

A filmmaker at the end of time and space

Giona A. Nazzaro

Boy meets girl at the end of the world. Once again, Julio Bressane stages the beginning of life itself as a stylized and dysfunctional yet mysteriously minnellian dance. O Garoto, element of the collective project Telha brilhadora, that comprises also O prefeito by Bruno Safadi, O espelho by Rodrigo Lima and Origem do mundo by Moa Batsow, is a film that has at its core a mischievous insurgent sexual energy that bristles and sparks relentlessly poetic hybris. Those who are not familiar with Bressane’s work may be puzzled by the minimalistic approach and its reiterative patterns, but it is obvious that O Garoto (The Kid) is just a different kind of educaçao sentimental. The boy and the girl inhabit a world whose only other sign of life is a rhythm pattern that seems to be almost detached from them, even though they watch and listen amused to the silent musician who keeps drumming away. The other element is the camera itself. The sensual geometries of the film try to make this triangle work. The camera wants to make love with the bodies in front of it. But the gaze of the girl and the boy point out toward the wilderness, a barren yet intoxicatingly magnificent landscape. This impossible triangle tries to claim hold of the land. Make it again a land of the living. Or, at least, they try to survive in and on it again. Let’s rewrite the social contract for the very last time. As it happens with Bressane’s recent work, O Garoto also recalls elements and patterns from his previous films. These fragments of memories and echoes from a different time are the tools with which Bressane shapes his vision. His newfound Adam and Eve are the sign of a never ending quest. To regain the world, that is the problem. As in O gigante da America, the film is also an arcane and bewildering reflection on the results of colonialism. O Garoto is definitely Bressane’s song of exile. His Paradise Lost, if you want. Minus the angels and the devils. Minus god. There is no regenerative utopia here. The two are destined to be apart. And even though the girl tries to break the diaphragm that separates her from the boy and the camera and the audience (the most sublime moment of the film), she is on her own as is the boy. Bressane films the end of the world as a reenactment of the origins of cinema: a boy and a girl. One plus one. Where the plus sign is obviously the camera itself. A precise yet restless camera, that roams a never before seen landscape as if it were the ultimate set of the world. A world that still hopes to be filmed, seen, and experienced as such. Bressane thus offers the image of a filmmaker at the end of time and space. Looking for signs of life, Bressane comes up with a sensual dance that manages to rethink the Lumière brothers filmmaking in an utterly innovative way.

INTERZONE – Rotolo armeno (Yervant Gianikian e Angela Ricci Lucchi)

Viaggio in Italia 1 - Conversazione con Franco Maresco

Viaggio in Italia 2 - Non essere cattivo (Claudio Caligari)

Ultimi articoli pubblicati

- 2025-03-24 Chime/Cloud/Serpent’s Path (Kurosawa Kiyoshi)

- 2025-03-24 Abiding Nowhere (Tsai Ming-liang)

- 2025-03-24 The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

- 2025-03-24 Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes)